Don’t be too comfortable. As an RPG that places you in the synthetic boots of escaped roboticons, the Citizen Sleeper 2 often runs. It is a crunchy and dangerous machine of vibrant and world-class construction, sometimes forgetting yourself with wandering prose. A compelling universe to sail, with more habitats and ho houses than its predecessors, more stations and stellar gateways. For me – I can’t escape the dense gravity of the compact storytelling of the first game and the new character building. But it’s a good time.

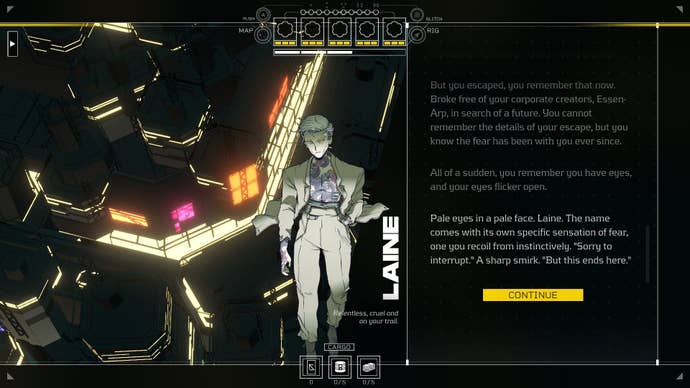

Once again, you play a biomechanical “bedroom” designed to work as slave labor. At the beginning of your story, you are challenging a crime boss called Laine. Rain is putting you under your thumb in exchange for a drug called stabilizers (injectable pickups are necessary to prevent all sleepers from deteriorating the body). But here we have a friendly Spacepal called Seraphine. Together on a stolen ship, explore the resident Shax belt, seeking to keep more distance between you and the abusive Rain.

Check out YouTube

The previous game was played with one spinning station, Erlyn’s eyes. But here, if you have fuel, you will gradually unlock the map, which is full of places to jump. There is a thin trade spire called The Far Spindle, where a water freighter bursts and requires emergency repairs. Or, in a fleet of ships called the Spray Garden, the sailors will pay you to draw advertisements on your ship. Or, on an asteroid called the Green Belt, the food is grown under unstable conditions across the belt.

By splitting the science fiction story into many of these little hubs, Citizen Sleeper 2 can feel a more sweep in its space drama. Each location offers a “contract” to send you to a bubble in nearby local space, including rescue of lost crews and collecting data from destroyed ships. But it can also feel deeper and more stylistic with each passing hub hop.

Perhaps this is all the way to expanding more cog-like components in the game. Again, I wrap the dice (basically) every morning at the beginning of each “cycle.” Slot these into different squares to perform the action. For example, if you can operate the shift with a 5 “dangerous” scrappy, you’ll probably be paid well, lose energy and not lose stress (2 meters that you need to juggle). Slot one into a “safe” activity, like a rest. Twos and Threes? Well, they are iffy. But we leave gambling and make another shift. Why is it not good? Contract missions also allow you to use additional chance cubes provided by fellow crew members.

However, dice can break under certain conditions and become unusable or “glitchy.” This means that there is a much greater chance of negative outcomes. Ideally, you can keep all the dice on track (you will meet an engineer who can bring them back into shape). But every dice can burst in one hopeless mission.

Five broken dices are tough, failing states that put you on the robot’s ass, leaving you with permanent, non-fixable glitch dice with each cycle. Something you definitely should avoid. It means you have less behavior every day. There may be fewer round loth soups, fewer stacking, fewer cargo shifts to pick up, and perhaps no dice time to explore the dangerous Shanti Town that spins in voids. The easiest mode of the game will withhold this punishment, so you can simply continue the story. The most difficult mode doesn’t even make you humorous. You simply ring it – Game Over, let’s start again.

The very fact that you have to spend this many paragraphs describing the dice shows that the system and item management feels greater this time (and also not mentions “supply”, class bonuses, dice, and various other currencies). Just like before, it’s a solid way to give the story some game bones. However, this significant emphasis on this technology can sometimes be overwhelming.

A more linear hub can feel that there is only one way of railroad distribution, especially in the case of a railroad. Just pump GambleBlocks into the only slot that seems important and it feels like you’re gambling with the story’s results, and the unforgettable narrative conclusions are clicked due to the flashy system that needs to be implemented everywhere. For me, these numerical systems were always less interesting than the characters and stories that circumnavigated them.

There are still many things people here who like. The character art has the bright styling of a well-thought-out comic book, with soft shadows falling on your face and endless creases of fabric that are not covered by zero gravity. If you’ve ever purchased a concept art book just to see what the artist designed before a modeler gets things in hand, then thank the person who stands up against the sparkling windows and drifting ships in a 3D animated background.

Importantly, when these characters speak, they feel alive. Lane is a vicious pusherman with the cruelty of slave owners, not to mention the ghostly pursuer whose voices have arisen in your mind at various intervals. In his eerie desire for complete control of your sleeper body, he classically hates if he’s ultimately diluted villain. Imagine Jessica Jones’ Kilgrave was poured into a glass with Harvey’s Splitz from the 2000s fugitive sci-fi show Farscape (a show that the game creators cite as an influence). Laine is just as systematic stressor as the storyful ones. It is often the case that a slightly red clock is exploring the hub that he is making a scent for you. You have to leave the dodge before he arrives.

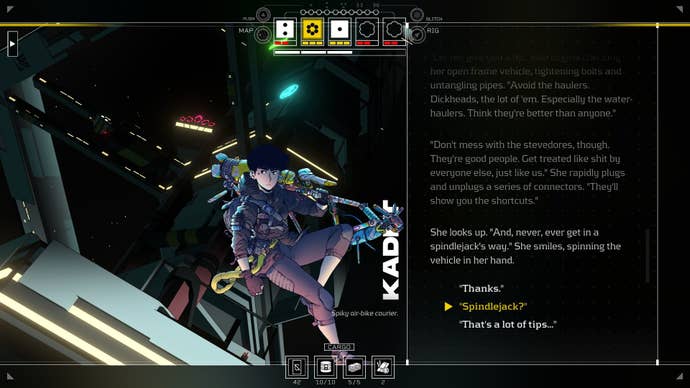

There are other memorable people. Nemba is a straight talk chef who might fire you from a part-time gig in his kitchen, but that’s because he has a cocky side mission in mind. Kadet is a leather-covered space biker who calmly saves your life from freight carriers and uses biker chick charisma to tie you down into dangerous data transactions. There are many more examples of such characters. But it is a temporary feeling that many people unite. Like you, these people are often moving and disappearing from your station, but will reappear in a distant hub a few hours later.

That said, they aren’t that convincing for me. Many of your sailors seem to suffer from “nice” doses. Disputes are easily resolved, and kindness is often given priority over conflict erupting. The drama expected of the Misfit crew shoved nearby on a spaceship will be set aside for quiet, family bonds. For many others, a kind crew might be the winner. But I know I’m not alone in craving one or two scumbags in a fictional ensemble.

Take, for example, Seraphine, the Savior. He is a heartfelt, capable pilot and a close friend of you throughout the game. I want a friend like him in real life. In the game, I wanted to get him out of the airlock. As your first companion, he plays the role of Mass Effect Starter Companion – the person who explains things to you and voices vanilla anxiety. He is strong and willing, caring, thoughtful and determined. I wanted to abandon him in the asteroid field a few hours later.

Instead, Serafin will accompany you along the main quest, which I am not as interested in as many different side gigs. I’ve even been annoyed by the handheld style of his story – I’ll often take you aside and tell you which Space Rock will be the perfect hub to visit next. It’s not Bethesda’s main quest character, but here’s the feeling of being shut down here, rather than whirling the world at your own pace, picking up the story you want and dropping others with Will after the relative loosening of the eyes that I really felt like I was in control of my wanderings.

To be fair, some of Shuttlestops are great adventures. Help the union organize an interstellar strike or dig into the shadowy streets of the Dark Side (the territory of scumbags belonging to the Rain). But I was expecting a more open-ended story from the start. By the time this freedom was given to you as a player, you basically looked at the whole system and met all the notes. Geographically it’s a wider game than the first one, but somehow I feel more trapped.

Don’t scare them. The scene is still well written, with expressive prose maintaining a good eye for body language and mannerism. Wipe your hands on the rags as the engineer speaks to you, the hacker kids betray the mysterious vulgar motives with their steely appearance. There is all the panaches of well-made genre fiction, but to maintain the rhythm of excellent interactive fiction, you will not overload you with a paragraph of lore. At the very least, this applies to most of the game. Later sequences can be shaky with abstract hacking and lengthy descriptions of space architecture. The game sometimes forgets to check for its own words of enthusiasm.

Thematically, it is faithful to its pioneer. The first citizen sleeper has turned the daring to interstellar capitalism to the heart of your story. You were a gig economy robot with a terrible addiction to repair drugs. A walking iPhone stretched out and escaped from the Apple Store. Starword Vector does not deviate from the theme of coercion under capital, except that it occasionally explores the fate of refugees fleeing war. It may also come from revisiting the strange forms that lead to having a body that truly does not feel your body, and realizing that you are not alone in such a struggle.

In all of this, it again steps the line between thoughtful speculative fiction and space sweeper-like popcorn sci-fi. I liked getting along with stray cats with zero gravity and summoning my previous biological self memories with a poetic passage about identity and comfort. But I also enjoyed meeting ancient drilling worms on the belly of a cursed asteroid.

It often turns it into something of your choice, with the long spool of main quests, the runaway passages that may be short, and the characters’ stories that sometimes feel like they’re hijacking your story.Their– Adventure. But Citizen Sleeper 2 can deliver heartfelt moments in a world of science fiction that feels more colorful than Starfield (again). Even if you still like noodles in Erlyn’s eyes, it’s finely crafted sci-fi.

Disclosure: Gareth Damian Martin, written for RPS by age developer Gareth Damian Martin